The Pain Remedy Big Pharma Doesn’t Want You to Know About

Some time ago, I knew a physical therapist named Sam who struggled with debilitating low back pain. This was particularly significant given how she was someone who helped people get out of musculoskeletal pain herself.

I was heartbroken to witness her struggle.

She was frustrated, as the pain seemed inexplicable and was recurring as time went on. She tried various things from her training as a PT to improve her situation. But if the pain lessened, eventually it came back.

Even breathing was painful for her.

We saw each other about five times over 2-3 months, and after we worked together for several sessions her pain was gone. Her stress lessened. She experienced emotional releases that she had not experienced before, like a pressure valve going off, and afterwards, she felt settled, centered, and able to move with less and less pain over time.

As her story suggests, the shift in her condition from pain to no pain was not the result of medication, a surgical procedure, or similar conventional approach. It also wasn’t acupuncture, Pilates, herbal supplements, hypnosis, reiki, or drinking more water.

This ultimate shift was an outcome of, simply, the breath.

The main thing I had her change was how she breathed.

This leads us to the question, what is it about the breath that can have a significant impact on pain?

Breath can inhibit health

Most people have basic knowledge about the breath. It’s an automatic part of our physiology. It helps us stay alive without us having to think about it. Breath keeps us going in the most tangible and immediate way.

However, breath is unique from other body systems in that it’s both automatic and voluntary, meaning a person can influence the way they breathe. Of course, we can’t hold our breath forever, because our bodies wouldn’t allow us to override its survival instinct. Eventually an inhale would happen.

There are many experts who weigh in on what they label as the proper way to breathe and suggest that one should never breathe through the mouth. Or that a long exhale is very relaxing.

But what if these sort of conventional ideas, when spoken as universal truths, could inhibit one’s health?

Or even impact someone’s life in a way that’s opposite to what they really want?

Many among us seek to use our breath as a way to grow and regulate ourselves. Breath is profoundly important tool to promote wellbeing in Eastern traditions such as yoga, qi gong, and tai chi.

I have even found that many yoga breath or pranayama practices to be very interesting and useful, but also potentially counter productive in our culture of high stress and anxiety.

This happened to me. I was so passionate about breath and had a pranayama practice for many years. I would attempt to use it to calm down, and did so one day when I was particularly wound up. But I started hyperventilating instead. This was particularly problematic for at that moment I was on the Interstate while driving 7 teenage boys home from a Halloween party past midnight.

I’d been a dedicated practitioner of yoga, devoted to a home practice, and I couldn’t see until then that what I had been doing was linked to that unfortunate moment. I did manage to get myself out of it. We made it home and I recovered.

My point is that breath, though we usually take it for granted, can at the very least be an indication of disorganized physiologic function. However, it can also be an indication of something of which we are depriving ourselves at a very fundamental level.

My experience with pain

There was a time when I woke up in so much pain I had trouble getting out of bed. I couldn’t bend over to tie my shoes. But it was the breath, awareness of it, and a growing mastery of it, bit by bit over time, that helped me emerge from this pain.

It wasn’t the only tool I used, but it was the key that unlocked a door to other forms of help. The breath helped other tools such as exercise and psychotherapy to work better too.

As breath practice started to become relevant in facing my own physical and emotional challenges, I practiced daily. Over time, I got well — more confident in my capacity to handle my life.

As I spent time with my mentors, and began working with others to facilitate therapeutic breath sessions with a variety of people, their pain went away too.

Many experienced mental clarity and a growing sense of wellbeing.

In one session, a person who had recurring back and rib pain from a domestic abuse incident didn’t feel it anymore. A man had neck pain from an automobile incident and it resolved. Another woman wanted to be able to walk upstairs without pain, and sit on the floor to play with her grandson, and she was able to do those activities with more ease.

Research is revealing that pain is not always related to acute events, especially when it comes to chronic discomforts that don’t seem to go away.

And the cause is often not just structural. One person may appear to have a beautiful posture yet suffer from chronic pain. Another person may be stooped over and twisted but happy and going about their life’s daily activities with minimal symptoms.

How can both those examples exist at the same time?

And given the apparent complexity of our relationship to pain, how can people like me and the physical therapist I mentioned overcome such maladies because of something as rudimentary as the breath?

A surprising discovery

We can begin to answer this question in response to a study conducted by German scientistis a few years ago that looked at the relationship between breathing and pain.

The researchers asked the question: can breathing influence how a person experiences pain?

The subjects were instructed in deep, slow breathing techniques, and some of them experienced a reduction in pain levels in response to the exercise.

However, not all of them did.

For some of the subjects, their pain level did not change. For others, their pain level increased.

These different outcomes were based on the kind of breathing they were assigned to do.

In the study, there were two different groups. Both groups were instructed to do the same deep and slow breathing method.

However, one group was asked to pay attention to an externally paced respiration with the help of monitor. They were given ideal breathing curve representing frequency and depth on a screen in front of them.

While they breathed, the ideal breathing curve and their own individual curve were presented side by side. This was similar to a biofeedback video game that one tries to win. The subjects were instructed to fit their own respiration curve to the ideal curve, which required constant attention and concentration on the breathing task.

They were instructed to come as close as they could to the ideal.

Given the precise, regimented nature of traditional breathing practices found in mindfulness, yoga, and other traditions, one would think that this precise, concentrated form of breathing corresponded with the group that felt a reduction in pain.

The papier mache example

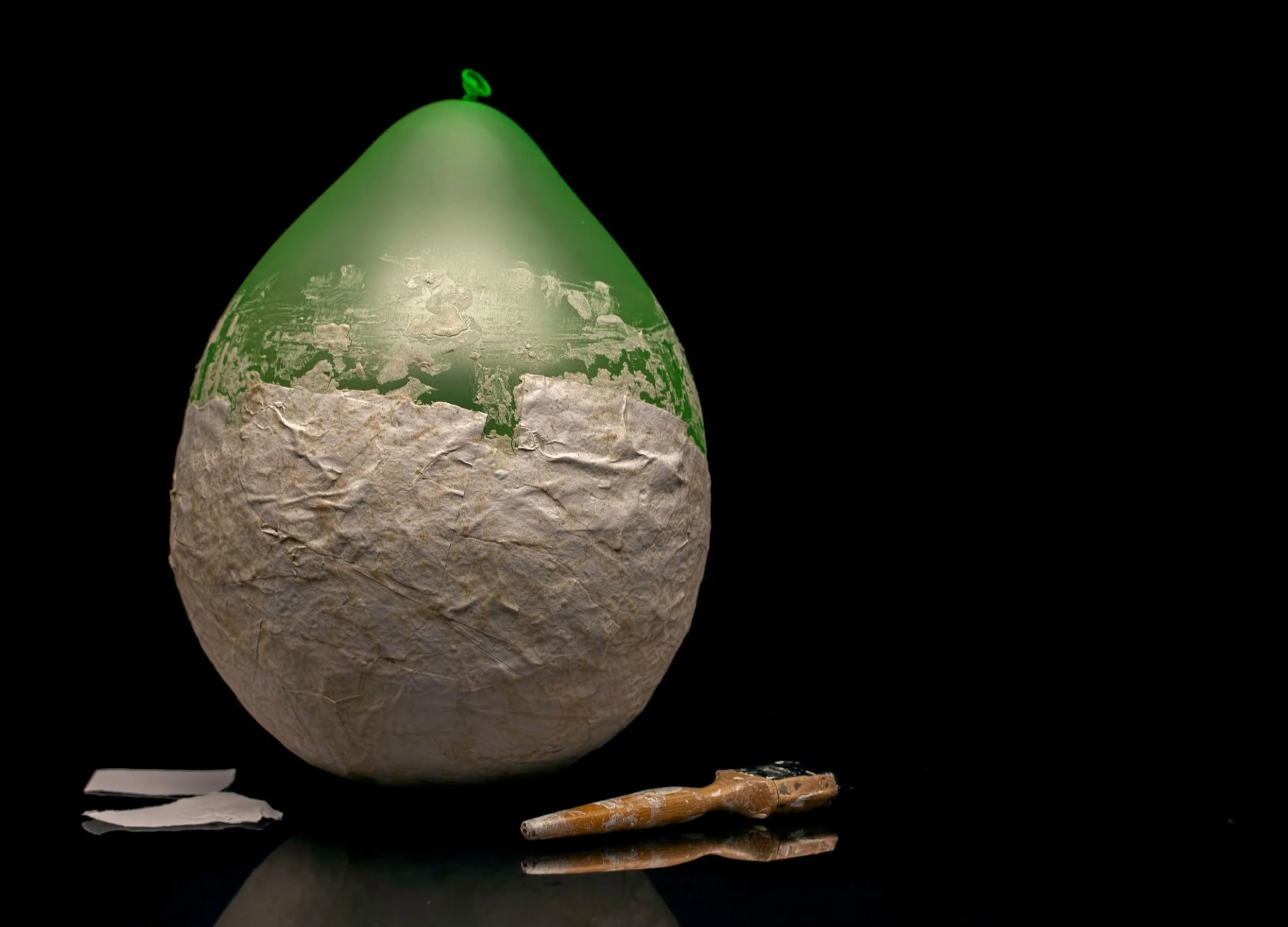

To investigate this assumption, we can look at the properties of papier mache. Did you ever play with this material as a kid? It’s soft at first and then you put it on a shape and it hardens, taking on the form of the shape to which it is applied.

Imagine if you applied fresh papier mache to the outside of the balloon. As it dries, it gets rigid. It imposes its hardened form on that of the balloon. This limits its expansion.

Similarly, anytime we impose ideals on the body we can potentially undermine our physiology. When we strive for this idea of perfection, we can impose a type of rigidity onto ourselves. This invites resistance, and overrides the body’s own way of being at any given time.

This can then increase the sensation of pain.

In this way, the externally focused paradigm of an attentive breath can potentially override the body’s instinct to perform its natural functions. This can potentially undermine our physiology.

It also requires additional cognitive effort to match our breath to the optimal pattern.

The problem with perfection

This fixation on perfection can imply that our own breath is sub optimal, imposing a negative judgement and even pressure and stress. This dissonance will run in the background of one’s mind while performing the task.

One might expect that by monitoring ideal conditions presented to half the participants – the half meant to match their breath to an ideal pattern – that this group would experience a reduction in pain.

We might think that they would enjoy the greatest outcome for the simple fact that they were apparently doing their given task right.

But this wasn’t the case at all.

As I mentioned earlier, in some cases their pain actually increased.

They hit the target for optimal breathing, but in the larger view of the study they failed.

Why?

To understand this, let’s take a look at the other group, which I haven’t told you about yet.

The other subjects used what they called a “relaxed” breath,” and they were told to direct their awareness on the experience of breathing itself.

They were not measured with biofeedback, and they were not looking at a monitor. The second group of subjects did not get visual feedback of their performance.

Instead they kept their eyes open, at a spot on the wall. They were guided in the same slow, deep breath technique that the first group used, but they were given permission to follow their internally felt-sense of how to do it.

Sense a relaxed breath

Remember our friend Sam from earlier? Before we started working together, she was a prime example of relating to the breath in an externally focused way.

I could see the restriction in her breath. In her case, she used a Pilates framework, which, similar to many athletics, proselytizes exhaling on exertion in order to stabilize the spine and strengthen the core. However, it can also override the body’s natural rhythm and healthy impulses in respiration.

She was using abdominal contraction in the form of cues such as knitting the ribs together, dropping the belly towards the spine, or exhaling all the breath out – all in service of strengthening her core.

However, our work together helped her to realize that this was having the opposite effect on her body over time.

These core strengthening techniques, while useful in certain situations, inhibited the movement of the diaphragm to move freely, and also created a muscle memory around breath that introduced repeated dysfunction farther and farther away from a natural breath.

Her pain was not the problem, it was the signal that something was not working.

And I wanted her to find her way back to what did.

There’s nothing wrong with this athletic breathing when used for specific situations, but this type of constriction pattern day after day is an example of a tensioning process we arrive at unconsciously.

The repetition of athletic breathing may start to feel normal and good. However, if it becomes your default way of breathing, it’s not normal, or good, even though it might feel that way.

For that very reason, the strategy is to become aware, to sense it, maybe even amplify the tension, just enough until you feel that it’s actually unpleasant and relating, perhaps even contributing, to the pain being felt.

Leaning into the discomfort of a dysfunctional breath pattern can help the body sense the contrast of a new and better way.

I worked with Sam to introduce a new, more natural pattern of breathing into her belly and relax her exhale.

I instructed her to breathe through her mouth during our work together, which you may have read from other experts is not a great thing to do. But mouth breathing worked very well given her particular tension in the body as it helped her to breathe so as to free up that tension.

This allowed for an ease that emerged directly from her internally-sensed practice, with some guidance and facilitation in the form of verbal and non-verbal cues such as touch and position changes.

The missing link in pain problems

In the research study, the group that followed this less directed pattern was referred to as using a relaxed breath. This was the group in the study that had the outcome of lowered pain perception which I mentioned earlier.

They experienced less pain because of the relaxed breath, and so did Sam.

Her breath awareness grew over time, leading to a domino effect of nervous system regulation, chemical balancing, lymphatic stimulation, and internal massage.

When I saw her some time later, she was recovered from 3 years of debilitating back pain. She reported that breathwork helped immensely as a missing link along with the physical therapy and pilates she credits with healing her low back pain.

I’ve seen this transformation occur for a person in just one session, and I’ve also seen it progress bit by bit over time, with people feeling less pain going forward.

Exploring a Different Way of Breathing

How might one go about exploring breathing in this way? It may seem like a paradox to breathe without instruction or direction being imposed on us yet still to fulfill an ideal. But below is an exercise to help you begin exploring this other way of breathing for yourself.

Watch your breath: Sit in a supported position against a wall or reclined on the floor. Close your eyes and observe your breath moving through your body.

Feel your breath: Place your hands on your tummy just below the belly button. Can you feel your belly rise and fall under your hands? Sense into it.

Invite a slower deeper inhale: Imagine your belly fills slowly like a balloon.

Relax the exhale: Do not push, control, or force air out. Let it go, just like letting air out of a balloon. It’s okay if you don’t exhale all the air out.

What might you to expect from this exercise? Its value comes from finding contrast between a natural breath and one in which you impose certain qualities on it.

Doing so will help you to be more effective at simply watching and sensing the breath. Letting go in this way can make it slower, deeper, and more nourishing.

And even 5 minutes of practice a day will help make it stick, so you can find it when you need it most.

Breath as the First Medicine for Pain Relief

We typically look at remedies like pain medicine and even more intense interventions like surgery in order to alleviate pain. But expanding breath awareness, and our felt-sense of it, empowers us toward a larger opportunity each of us has to not only enjoy a cost-free remedy with little chance of side effects, but to tap into something even more profound.

To be with our breath in this way is to reclaim natural forces of tension and release. It enables us to work with a natural intelligence that guides us to make better and wiser choices in our lives.

Breath is not only the first medicine we use in response to pain, it empowers us to trust in our capacity to live. Not only is it free from side effects, but it comes from the greatest resource we have: ourselves.